The first clinical trial injecting fetal stem cells into babies in the womb will start in January and will be led by Sweden’s Karolinska Institute and in the UK by Great Ormond Street Hospital. The stem cells will come from terminated pregnancies. It is hoped the cells, which are able to transform into a range of tissues, will lessen symptoms of incurable brittle bone disease.

Severe brittle bone disease is rare but can be so devastating that many women decide to end their pregnancy on being told their baby has the condition. In most cases, the brittleness is caused by a defect in the gene that makes collagen, the main building block of bone. Bones are so fragile that they can break while still in the womb and a child can suffer hundreds of fractures throughout life. Most children will become confined to wheelchairs, life expectancy is shortened, and they can also suffer other problems from deafness to heart disease.

There is no cure for the disease, and bone-strengthening drugs, metal rods and physiotherapy are the mainstays of treatment. So far, only two children in the world have been treated in the womb, with promising results. Both babies tolerated the stem cells well, and one, a girl who is now 13, has been able to take up dancing and gymnastics. However, an actual trial involving a bigger number of babies is needed to judge the treatment’s worth. Fifteen babies will be given a jab of stem cells around halfway through pregnancy.

Brittle bone disease, officially called osteogenesis imperfecta, affects around one in every 25,000 births. It can be fatal with babies born with multiple fractures. Even those who survive face up to 15 bone fractures a year, brittle teeth, impaired hearing and growth problems. It is caused by errors in the developing baby’s DNA , their blueprint of life that mean the collagen supposed to give bone its structure is either missing or of poor quality. The donated stem cells should provide the correct instructions for growing bone.

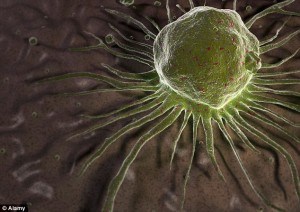

The stem cells, ‘master cells’ able to carry out a variety of functions will home in on the bones and produce the collagen needed to strengthen them. Top-up jabs will follow for the first two years of life and the children will be compared with untreated youngsters. It is hoped that starting the treatment in the womb, before the bones become too damaged, will make it extra-effective.

Prof Lyn Chitty, from Great Ormond Street Hospital, will carry out genetic testing to search for the defects that lead to the condition. She told the BBC News website: “This is a very serious disease. Our objective is to see if in utero (in the womb) stem cell therapy can ameliorate the condition and the number of fractures.” A type of stem cell which develops into healthy bone, cartilage and muscle will be infused directly into the affected foetuses. Fifteen babies will have the infusion in the womb and again after they are born. A further 15 will only have the treatment after birth and the number of fractures will be compared with untreated patients.

Stem cell transplants appear to ease symptoms in children. Starting even earlier when the bone is developing and growing rapidly has the potential to be more effective. “In-the-womb” foetal stem cell transplants have been tried in two cases of osteogenesis imperfecta. But without a proper clinical trial it is impossible to know how effective the therapy is. Dr Gotherstrom added: “It is the first in-man trial and, if successful, it will pave the way for other prenatal treatments when parents have no other option.” She said muscle disorders such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and other bone disorders could one day benefit from such therapies.

The first infusion will take place 20 to 34 weeks into the pregnancy. This is after the gonads have formed and there should be no risk of the donated cells becoming part of the recipient’s sperm or eggs. Any risk of the donated tissue being rejected in the same way as an organ transplant is thought to be low. Commenting on the trial, Dr Dusko Ilic, a reader in stem cell science at King’s College London, told the BBC: “Any attempt to help the patients suffering this terrible, debilitating disease is more than welcome.” However, he warned the disease varied so widely from patient to patient that it could be difficult to prove how effective the stem cells were. He added: “People with the same type of osteogenesis imperfecta may present a different clinical picture, even within the same family.”At the same time, cellular therapy is unlikely to work to the same extent in different individuals.

Professor Raymond Dalgleish, a Leicester University geneticist involved in the Swedish-led trial, said: ‘This is an exciting project with the potential to provide much improved quality of life for children affected by severe forms of this disorder.’ Benjamin Jacobs, an expert on the condition and a spokesman for the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, said that while he doesn’t expect the stem cell jabs to be a cure, an improvement in quality of life would be a major step forward.

For more information please visit: http://ki.se/start