Harmful chemicals, stress and other influences can permanently alter which genes are turned on without changing any of the genes’ code. Now, it appears, some of these “epigenetic” changes are passed down to—and may cause disease in—future generations.

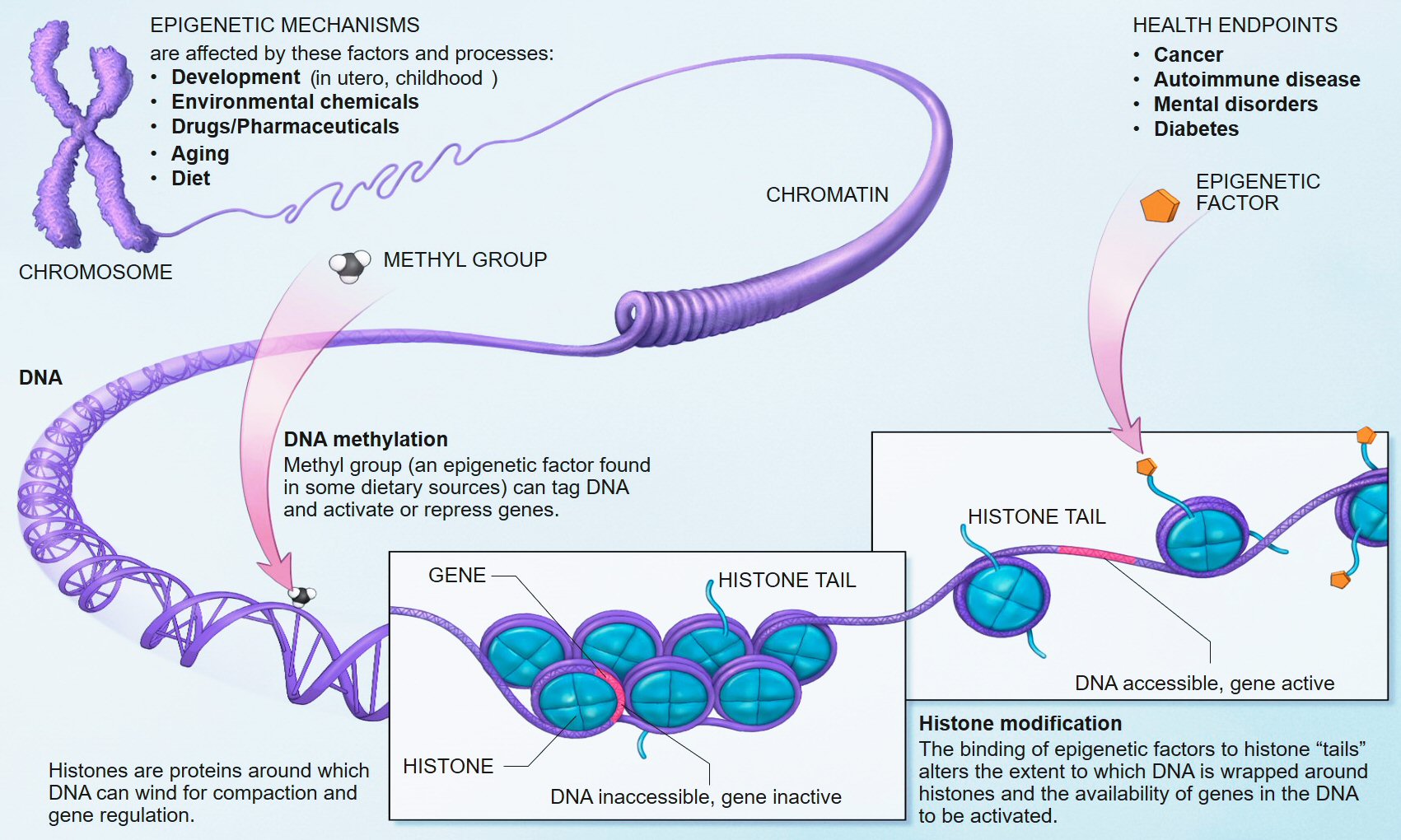

Epigenetics studies genetic effects not encoded in the DNA sequence of an organism, hence the prefix epi- (Greek: επί- over, outside of, around).Such effects on cellular and physiological phenotypic traits may result from external or environmental factors that switch genes on and off and affect how cells express genes. These alterations may or may not be heritable, although the use of the term epigenetic to describe processes that are heritable is controversial.

Our biological bequest to our children includes more than just our DNA sequences—that, indeed, not just our kids but our grandchildren and great-grandchildren might inherit what is known as epigenetic information. Like DNA, epigenetic information resides in our chromosomes (which house our genes) and regulates cellular functions. But it is distinct from the DNA sequence and responds to the environment. It can take various forms, including small molecules that attach chemically to the DNA and to proteins in chromosomes.

Research at my laboratory and others, mainly on rats and mice, has found that certain pollutants—including agricultural chemicals, jet fuel and even some common plastics—can induce epigenetic modifications that cause disease and reproductive problems, all without changing the sequence of the animals’ DNA. More startlingly, when such epimutations occur in the cells that give rise to eggs and sperm, they can apparently become fixed in place and then transmitted—along with any resulting health risks—to later generations.

The science in this area is evolving rapidly, and long-term studies in people now hint that epimutations may pass from generation to generation in humans as well. Given the many aspects of biology that we share with other mammals, it seems reasonable to expect that such epigenetic transgenerational inheritance does occur in people. If so, the implications for public health could be profound. Some part of the increases in obesity, diabetes and other fast-rising diseases among baby boomers and more recent generations might have originated with their parents’ and grandparents’ exposure to pollutants such as DDT and dioxin.