Atrial fibrillation is a heart rhythm disorder that affects millions of people. It can make you feel lousy. Even worse, it can cause potentially disabling or deadly strokes. A special MRI scan may help identify people with atrial fibrillation who are at high risk of having a stroke. This could help many people with this condition to avoid taking warfarin or other clot-preventing medications for life.

A normal heartbeat starts in a cluster of cells called the pacemaker. It sits in the heart’s upper right chamber (the right atrium). These cells generate a pulse of electricity that flows to the rest of the heart and causes a coordinated heartbeat. In people with atrial fibrillation, electrical signals arise from areas outside of the pacemaker. These signals are fast and irregular. So instead of contracting with a steady rhythm, the right and left atria quiver. This can allow blood to pool in the atria instead of flowing smoothly through the heart and into the body. When blood pools in the atria, it can form small clots. If one breaks away from inside the heart and gets into circulation, it could lodge in the brain, causing a stroke.

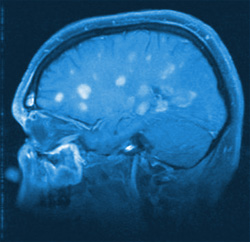

To reduce the risk of stroke, people with atrial fibrillation are often advised to take a blood thinner like warfarin or one of the newer alternatives, dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), or apixaban (Eliquis). But blood thinners can cause severe and sometimes life-threatening bleeding.Researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine wanted to see if imaging could identify people with atrial fibrillation who were at high stroke risk. They performed standard MRI scans of the hearts of 149 men and women with atrial fibrillation, then used special motion-tracking software to evaluate the images. The scans revealed specific changes in the muscles of the left atrium that increased stroke risk in some of the volunteers.

Experts have devised a tool called the CHA2DS2-VASc Score to calculate stroke risk for people with atrial fibrillation. It estimates this risk by taking into account age and sex, the presence or absence of heart failure, high blood pressure, narrowed blood vessels, and diabetes; and whether you’ve had a previous stroke, TIA, or blood clot. A low score indicates that warfarin or other clot-preventing medicine may not be needed.The irregular heartbeat can increase the risk of stroke, but it’s difficult to pinpoint which of the estimated 6 million Americans with atrial fibrillation are at high risk for stroke and should be put on blood-thinning drugs.

In the new study, the team led by Dr. Hiroshi Ashikaga, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, used special motion-tracking MRI scans on 169 patients with atrial fibrillation, aged 49 to 69. The test combined standard MRI scans with motion-tracking software that analyzes heart muscle movement, the team explained. The study revealed that a specific alteration in the function of the left atrium, one of the heart’s four chambers may be a sign of stroke risk. “Our research suggests that certain features of the heart’s upper left chamber that are easily seen on heart MRI could be the smoking gun we need to tell apart low-risk from high-risk patients,” Ashikaga, an assistant professor of medicine and biomedical engineering at the school, said in a Hopkins news release.

Being able to identify atrial fibrillation patients at high risk for stroke is important, the researchers said, because it would help doctors weigh stroke risk against the serious side effects posed by prescribing blood thinners to reduce that risk. It’s not clear why altered function in the left atrium increases stroke risk, but it may be linked to slower blood flow that increases the risk of blood clots that can lead to stroke, the researchers said.

“Altered function in the left atrium of the heart may lead to stroke independently of the heart rhythm disturbance itself,” explained Dr. Joao Lima, a professor of medicine and radiology at the medical school and director of cardiovascular imaging at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He and Ashikaga believe this altered heart chamber function could occur even in people without atrial fibrillation. “Maybe when it comes to stroke risk and afib, we’ve been chasing the wrong guy all along,” Ashikaga said. “Maybe atrial fibrillation itself is not the real culprit and dysfunction of the left atrium is the real baddie. It’s a possibility we have to consider and will in an upcoming study.”

Cardiac MRI “now also appears to have the potential to predict which patients with atrial fibrillation will be at increased risk for a stroke,” said Dr. Juan Gaztanaga, director of advanced cardiac imaging at Winthrop-University Hospital in Mineola, N.Y. If proven successful, the technology “would allow us to identify higher risk patients and treat them more aggressively, and at the same time not expose low risk patients to blood thinners,” he said.

For more information please visit: www.harvard.edu

Comments are closed.