Scientists at University of Bristol are developing soundproof wallpaper inspired by moths wings. Experts at the University of Bristol have discovered that the scales on moth wings act as excellent sound absorbers even when placed on an artificial surface.

The University of Bristol team found the phenomenon holds the key to better sound-absorbing panels. It will revolutionize noise-canceling technology, they say.

Co-author Professor Marc Holderied explained: “This research has shown one day it will be possible to adorn the walls of your house with ultrathin sound absorbing wallpaper, using a design that copies the mechanisms that gives moths stealth acoustic camouflage.

“What we needed to know first, was how well these moth scales would perform if they were in front of an acoustically highly reflective surface, such as a wall.

“We also needed to find out how the mechanisms of absorption might change when the scales were interacting with this surface.”

Noise pollution is the second largest environmental cause of health problems, just after the impact of air quality.

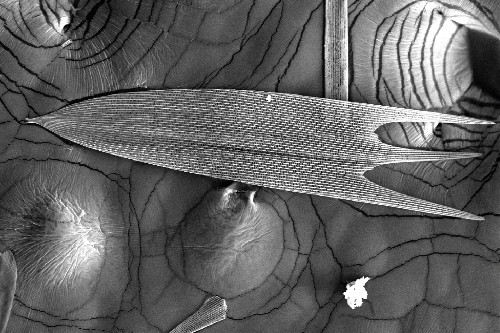

he researchers, which recently discovered that moth wings offer acoustic protection from bat echolocation calls, have been studying whether their structure could inform better performing sound absorbing panels, when not moving in free space.

Bats and moths have been involved in an acoustic arms race between predator and prey ever since bats evolved echolocation some 65 million years ago. Moths are under huge predation pressure from bats and have evolved a plethora of defences in their strive for survival, but it’s the scales, on a moth wing, that hold the key to transforming noise-cancelling technology.

Prof Holderied and his team tested this by placing small sections of moth wings on an aluminium disc, then systematically tested how orientation of the wing with respect to the incoming sound and the removal of scale layers affected absorption.

Remarkably, they found that moth wings proved to be excellent sound absorbers, even when on top of an acoustical solid substrate, with the wings absorbing as much as 87% of the incoming sound energy. The effect is also broadband and omnidirectional, covering a wide range of frequencies and sound incident angles.

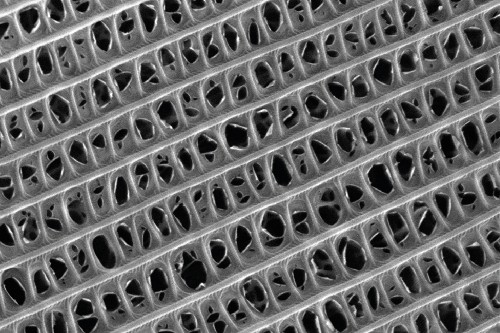

“What is even more impressive is that the wings are doing this whilst being incredibly thin, with the scale layer being only 1/50th of the thickness of the wavelength of the sound that they are absorbing,” explained lead author Dr Thomas Neil. “This extraordinary performance qualifies the moth wing as a natural occurring acoustic absorbing metasurface, a material that has unique properties and capabilities, that are not possible to create using conventional materials.”

The potential to create ultrathin sound absorbing panels has huge implications in building acoustics. As cities get louder, the need for efficient non-intrusive sound mitigation solutions grows. Equally, these lightweight sound absorbing panels could have huge impacts on the travel industry, with any weight saving in planes, cars and trains increasing efficiency in these modes of transport, reducing fuel use and CO2 emissions.

Now the scientists plan to replicate the sound absorbing performance by designing and building prototypes based on the sound absorbing mechanisms of the moth. The absorption that they have characterised in moth wing scales is all in the ultrasound frequency range, above that which humans can hear. Their next challenge is to design a structure that will work at lower frequencies whilst retaining the same ultrathin architecture employed by the moth.

Prof Holderied concluded: “Moths are going to inspire the next generation of sound absorbing materials.

“New research has shown that one day it will be possible to adorn the walls of your house with ultrathin sound absorbing wallpaper, using a design that copies the mechanisms that gives moths stealth acoustic camouflage.”

Paper:

‘Moth wings as sound absorber metasurface’ by Thomas R. Neil, Zhiyuan Shen, Daniel Robert, Bruce W. Drinkwater and Marc W. Holderied in Proceedings of the Royal Society A.

Credit : https://www.bristol.ac.uk/