Scientists find way to disarm deadly bacteria without destroying the good ones in your gut.

The new discovery of a drug that blocks the intestinal pathogen without killing resident, beneficial microbes may prove superior to antibiotics, currently the front-line treatment for infection.

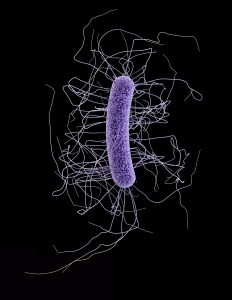

Nearly half a million Americans get infected in a single year by Clostridium difficile, a dangerous bacteria that causes life-threatening diarrhea. It kills 15,000 people a year. It’s the most common cause of health-care associated infections in U.S. hospitals.

Patients on antibiotics are at the greatest risk for developing C. diff infections. That happens when people are prescribed powerful antibiotics incorrectly or unnecessarily.

These antibiotics wipe out the good bacteria normally inside in your gut that protect you against infections. That’s when vulnerable patients can get a C. diff infection from a contaminated surface or from another person.

Researchers from Stanford say they have found a way to disarm a C. diff toxin that makes people sick, but in a way that doesn’t harm those good gut microbes.

By not aiming to kill the pathogen with antibiotics, scientists were able to avoid wiping out sizeable numbers of beneficial gut microbes.

This new treatment allows you to treat the symptoms without using a broad spectrum antibiotic that also kills off the good bacteria in the gut. The study uses a drug-like molecule called ebselen.

The study was done in mice, but researchers say it could be moved quickly into human trials because ebselen is already being tested in clinical trials to treat other, unrelated conditions.

Experts say the findings add to several encouraging approaches to fighting an infection that recurs in 1 out of every 5 patients who get it.

An experimental antibody was shown to significantly reduce the recurrence of C. diff infections, according to results presented by the company at a recent medical meeting in San Diego.

They are also developing a vaccine that directs the immune system to produce antibodies against C. diff toxins. Another study has shown that giving a nontoxic strain of C. diff appears to protect against recurrence of infection.

Current treatments for C. diff infections include stopping antibiotics, using appropriate antibiotics, and fecal transplants, in which the bacteria from a healthy gut are implanted into an unhealthy one.

The process involves a compound called ebselen which is used to target a toxin produced by C. diff. Ebselen is already being used in clinical trials for chemotherapy-related hearing loss and stroke and preclinical testing shows that it is safe and tolerable.

Researchers treated the mice with multiple rounds of antibiotics, then introduced a virulent, multi-drug-resistant strain of C. diff. Then they gave the mice oral doses of ebselen. They found a nearly complete block of inflammation and damage to colon tissue as a result of the ebselen treatment. The ebselen disabled the toxin’s.

The molecule is not expensive to make so researchers can move rapidly into clinical trials for treating C. diff infections.

For more information please visit: www.med.stanford.edu