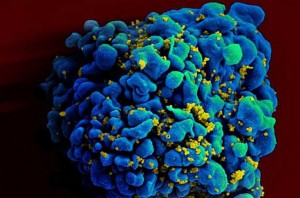

Scientists have discovered that HIV has a voracious sweet tooth, which may be its Achilles’ heel, reports a new study from Northwestern Medicine and collaborators. After the virus invades an activated immune cell, it craves sugar and nutrients from the cell to replicate and fuel its wild growth throughout the body. Teams from Northwestern University and Vanderbilt University have reportedly discovered a way to block the virus from feasting on the glucose in an infected patient’s bloodstream.

Scientists discovered the switch that turns on the immune cell’s abundant sugar and nutrient pipeline. Then they blocked the switch with an experimental compound, shutting down the pipeline, and, thereby, starving HIV to death. The virus was unable to replicate in human cells in vitro.

When a person contracts the virus, HIV quickly moves through the bloodstream, targeting CD4+ T-cells, which are the leading cells of our immune system. The virus immediately begins to steal the glucose supply of the immune system cell, allowing the virus to replicate. In this study, the teams used a compound to block the immune cell’s pipeline of nutrients, including glucose. With HIV cells effectively cut off, its ability to reproduce is negated. Effectively, its sweet tooth is its downfall.

It is a promising study. It cuts HIV off, and the researchers were able to block HIV’s source of energy without harming healthy cells. Human trials are a ways off, but the hope is it can lead to HIV treatments that do not rely on drug protocols. It can help prevent drug resistance, and offer doctors another tool to battle HIV. It could also offer novel treatments for cancer patients in the future too. Cancer cells thrive on access to glucose in the bloodstream. Treatments that can cut them off from their energy source, while not harming healthy cells, could revolutionize treatments across a spectrum of diseases.

HIV needs to grow in a type of immune cell (CD4+ T cell) that is active, meaning it is already responding to pathogens in the blood. Activation increases the T cell’s supplies of sugar and other critical nutrients needed for both cell and virus growth. Until now, no one knew the first step that signaled a newly activated T cell to stock up on sugar and other nutrients. Those nutrients become the building blocks of genetic material the cell and the virus need to grow. Northwestern and Vanderbilt scientists figured out that first step in stocking the T cell’s pantry involved turning on a cell component called phospholipase D1 (PLD1). Then they used an experimental compound to block PLD1 and shut down the pipeline.

“This is just the beginning of an exciting line of investigation for our group,” Taylor says. “We are actively searching for other compounds that inhibit HIV in a similar fashion.” New research is offering hope to the 50,000 people the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, infects every year.

For more information please visit: www.northwestern.edu