Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators have identified specific EEG (electroencephalogram) signatures that indicate when patients lose and regain consciousness under the general anesthetic drug propofol. The study reveals brain patterns produced by the general anesthesia drug which could help doctor’s better monitor patients.

“We have discovered highly structured EEG patterns that indicate when people are sedated during administration of propofol, when they are unconscious and when they are able to regain consciousness,” says Patrick Purdon, PhD, of the MGH Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, lead author of the PNAS report. “These findings provide precise, neurophysiologically principled markers that can be used to monitor the state of a patient’s unconsciousness under propofol general anesthesia.” Although it has been known since the 1930s that certain general anesthestics produce typical pattern changes in EEG, recordings of the brain’s electrical activity taken by electrodes placed on the scalp and specific patterns that indicate the loss and recovery of consciousness under anesthesia have never been identified. Monitoring of patients under anesthesia has focused on tracking vital signs such as changes in heart rate and blood pressure. Dosing of anesthetic drugs has been based on target or measured concentrations in the blood or the lungs, even though the primary effects of the drugs are in the brain and central nervous system.

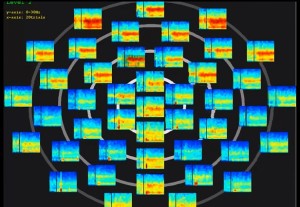

Although the raw EEG and its frequency components can give direct, detailed information about brain states under anesthesia, Purdon explains, most current brain monitoring systems reduced the complex EEG signal to a single number that could not accurately reflect the underlying physiological processes that create the patterns. Indeed clinical studies have found current depth-of-anesthesia monitors to be no more effective at predicting awareness than monitoring drug levels in the lungs.

The current study took highly detailed EEG readings of 10 healthy volunteers during propofol general anesthesia. When used clinically, propofol usually induces unconsciousness within less than a minute, making detailed tracking of EEG changes virtually impossible. But for this study, propofol dosage was slowly increased to a target level over a period of one hour, then slowly decreased over a second hour. During that time, study participants listened to prerecorded sounds, either words or clicks presented every four seconds and were asked to identify the type of sound they heard by pressing a button. A loss of response to clicks indicated the onset of sedation, and a persistent loss of response to words was considered loss of consciousness. The readings taken throughout the two-hour study period identified changes in EEG patterns that indicated sedation, loss and return of consciousness, and a state of profound unconsciousness.

An important observation related to interactions between the signaling frequencies measured by EEG. One particular pattern, which the researchers call “trough-max,” occurred during transitions in consciousness, particularly right before consciousness returned. Another pattern called “peak-max” was observed at the highest propofol dosage and signified the deepest levels of unconsciousness. Purdon and his colleagues believe that the peak-max signal pattern corresponds with the brain state identified in the November PNAS Plus report, which represented a disruption in communication between different parts of the brain. “The consequences of this could be huge, because it would mean we have found a brain state where we know patients will be unconscious and could monitor that brain state in the operating room using EEG,” Purdon says. “Appearance of the trough-max pattern would provide a way to predict when patients might be regaining consciousness. With these fundamental neurophysiological markers of the sedative and unconscious states under propofol and with some existing EEG equipment, we can start monitoring these EEG signatures when administering propofol immediately.”

An instructor in Anesthesia at Harvard Medical School, Purdon adds, “We are working on new monitoring technologies to develop of EEG monitors that will display the peak-max and trough-max patterns, helping us ensure when patients are unconscious and predict when they might be regaining consciousness. We also are working to characterize similar EEG patterns for other anesthetic agents and to develop a program to train anesthesiologists how to interpret the EEG in terms of the neurophysiology and mechanisms for different drugs.”

For more information please visit: www.mit.edu