A simple blood test may be able to predict cancer years before a diagnosis.

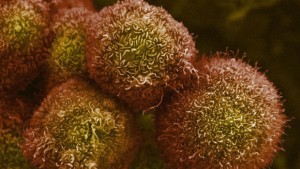

A distinct pattern in the changing length of blood telomeres, the protective end caps on our DNA strands, can predict cancer many years before actual diagnosis, according to a new study from Northwestern Medicine in collaboration with Harvard University.

“Understanding this pattern of telomere growth may mean it can be a predictive biomarker for cancer,” Dr. Lifang Hou, the lead study author and a professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said in a statement. “Because we saw a strong relationship in the pattern across a wide variety of cancers, with the right testing these procedures could be used to eventually diagnose a wide variety of cancers.”

For years, scientists have been trying to understand the relationship between telomeres, considered a marker of biological age, and cancer development. Previous results, however, have been inconsistent.

The pattern, a rapid shortening followed by a stabilization three or four years before cancer is diagnosed could ultimately yield a new biomarker to predict cancer development with a blood test.

Scientists have been trying to understand how blood cell telomeres, considered a marker of biological age, are affected in people who are developing cancer but the results have been inconsistent, some studies find they are shorter, some longer and some show no correlation at all.

In the new study, scientists took multiple measurements of telomeres over a 13-year period in 792 persons, 135 of whom were eventually diagnosed with different types of cancer, including prostate, skin, lung, leukemia and others.

Initially, scientists discovered telomeres aged much faster (indicated by a more rapid loss of length) in individuals who were developing but not yet diagnosed with cancer.

Scientists gathered that telomeres aged more quickly, indicated by a more rapid loss of length in the individuals who were developing cancer.

In these people, the telomeres appeared as much as 15 years older than those who were not developing the disease.

The study also found that the accelerated aging of the telomeres stopped three to four years before the individuals were diagnosed with cancer.

This is believed to be the first study to explore telomere length at more than one point in time before cancer diagnosis.

Cancer treatment may shorten telomeres so it is uncertain how their length is affected by cancer itself or the treatment.

Researchers say this is likely why previous studies have been so inconsistent. “We saw the inflection point at which rapid telomere shortening stabilizes,” Hou said. “We found cancer has hijacked the telomere shortening in order to flourish in the body.”

Telomeres in persons developing cancer looked as much as 15 years chronologically older than those of people who were not developing the disease.

Scientists then found that the accelerated aging process stopped three to four years before the cancer diagnosis.

Understanding this pattern of telomere growth may mean it can be a predictive biomarker for cancer

As there is a strong relationship in the pattern across a wide variety of cancers, with the right testing these procedures this could be used to eventually diagnose a wide variety of cancers.

The Northwestern and Harvard study is believed to be the first to look at telomere length at more than one time point before diagnosis.

That’s significant because cancer treatment can shorten telomeres. Post treatment, it’s uncertain whether their length has been affected by the cancer or the treatment.

This likely explains why the previous studies have been so inconsistent.

Scientists saw the inflection point at which rapid telomere shortening stabilizes and found cancer has hijacked the telomere shortening in order to flourish in the body.

Telomeres shorten every time a cell divides. The older you are, the more times each cell in your body has divided and the shorter your telomeres.

Because cancer cells divide and grow rapidly, scientists would expect the cell would get so short it would self-destruct.

But that’s not what happens, scientists discovered. Somehow, cancer finds a way to halt that process.

If scientists can identify how cancer hijacks the cell, Hou said, perhaps treatments could be developed to cause cancer cells to self-destruct without harming healthy cells.

For more information please visit: www.northwestern.edu